Event reports 2019

SANHS Low Ham History Day 19th November 2019

David Victor – SANHS historian

DV introduced the day with a tale of financial madness brought on by one John Stawell who attempted to build a palatial country house at Low Ham, with a façade 400 feet long, having demolished two fine country houses in so doing and a great inheritance. The building begun in 1689 was unfinished: the profligate baron, who had come into great wealth with 20 manors in his estate including Somerton, Aller and lands in West Somerset, unfortunately died aged 23 in 1692. He left large debts (to be paid off by Act of Parliament) and a wife who proceeded to dispose of his assets, large and small.

The story as told by David was a lot more complicated and involved the amassing of the estates in the first place by Sir Edward Hext, confiscation after the Civil War and then restitution at the Restoration together with the creation of a baronry for his son Ralph Stawell by the grateful monarch. Quite a tale! The triumphal arched gateway which stands just off Sparkford High Street came from Low Ham Manor but nothing now remains of the grand house itself. Julian Orbach in his reworked Pevsner1, reports that John Stawell spent more on the house than was spent on Calke Abbey or Buckingham House in London. Even decades later, when it was described as ‘vast piles of a stately ruin’, the painted ceilings were still in evidence.

Rob Wilson-North – Exmoor National Park

This snapshot of the fortunes of Low Ham in the seventeenth century was very germane to a discussion presented by Rob Wilson-North who had studied the gardens at Low Ham as a student and later on for the RCHM2. No descriptions or sketches or maps survive of the gardens which were partly Hext and partly Stawell, although Jacob Bobart the younger wrote a letter at some point setting out how the gardens should be laid out.

All that survives are the earthworks (Figure 1) which present a curious mix-up. The gardens run downhill and the church (of which more later) can be seen at the northern end, but the locations of the great house and the former substantial family properties remain undocumented.

The earthworks comprise a series of terraces which can be seen in the centre of the image and a massive 12 foot wall runs down the eastern side. Further to the east are less well-defined terraces set at an angle, while to the west are more terraces which are only half dug out so their purpose isn’t very clear – were they excavated as quarries or just unfinished like so much else ascribed to John Stawell? The terraces to the east are puzzling as they make the gardens into a wedge design, which looks unbalanced. However, similar slightly trapezoid shapes can be found elsewhere (Gamlingay in Cambridgeshire, Cerne Abbas in Dorset) so that in itself isn’t a mystery. In any case, Rob emphasised that the whole setting just does not make sense without knowing how the great house commanded the prospect. At the bottom of the slope lies the church which as a quite modest affair was hardly going to represent the focus of a grand garden design.

Julian Orbach – architectural historian and vice-president of SANHS

For Julian, the setting of the church at Low Ham (Figure 2) is just one of its anomalies. For those unfamiliar with the church, it sits in a field on its own without the trappings of a village church (Low Ham is not a parish) and without a dedication.

Edward Hext bought the Low Ham estate in 1588 and died in 1623 and was buried in the church which indicates that the church was at least partially completed by then. While the church is Somerset perpendicular in style and so relates nicely to being built in the late sixteenth century, the period of construction is unclear as there are many oddities featured in the building – the tracery in the Gothic windows for instance, the arched mouldings and carved inscriptions inside the church as well as dates of consecration put it firmly in the seventeenth century. Julian went more strongly for the earlier dates but clearly it was a work in progress for some considerable time. For a more considered description of the church, it is worth looking at Julian’s work on Somerset.1 op cit.

A review in the Church Times from 2008 of a book by Annabel Ricketts casts a different light. Her study on English country house chapels outlined in meticulous detail how and why the aristocracy and gentry of the 17th-century provided their houses with places of worship after the upheavals of the Reformation. The question precisely why such chapels were considered necessary had been posed by W. Gibson in 1997, who said that ‘chaplains, like libraries and chapels . . . were part of the mental landscape of the landowning élite’. Thus they were more architectural adjuncts to a great house than a necessity, in the same way as today’s fashion is for indoor swimming pools.2

Roger Leech – Southampton University

However, in Roman times, the bath house was a statement of having it all, perhaps. We now arrive at the late Roman villa site. Roger Leech gave a summary of the historiography of the excavations carried out at fourth century Low Ham villa. The villa is best known for the mosaic which depicts scenes from Virgil’s Aeneid and can be seen in all its glory at the museum in Taunton. He showed a prodigious selection of photographs from the late 1940s and early 1950s excavations which were really fascinating. The site was presented as clean as a whistle with not a trowel or bucket in sight. He also showed drawings of the excavation from 1949 and discussed the nature of the building, which was a wealthy courtyard villa.

The early excavations focussed on the bath house (Figure 3) and the west wing of the villa. A lot of fourth century pottery was found, particularly BB1 black burnished ware. The key figures were Herbert Cook who discovered the site, Lionel Waldron who was involved with the excavations and HSL Dewar and Ralegh Radford who directed them.

This link is from Pathe News and shows the excitement at the discovery of the mosaic. Much of what Roger included will form part of the final Historic England report on Low Ham which will also take account of the recent work.

David Roberts – Historic England and Cardiff University

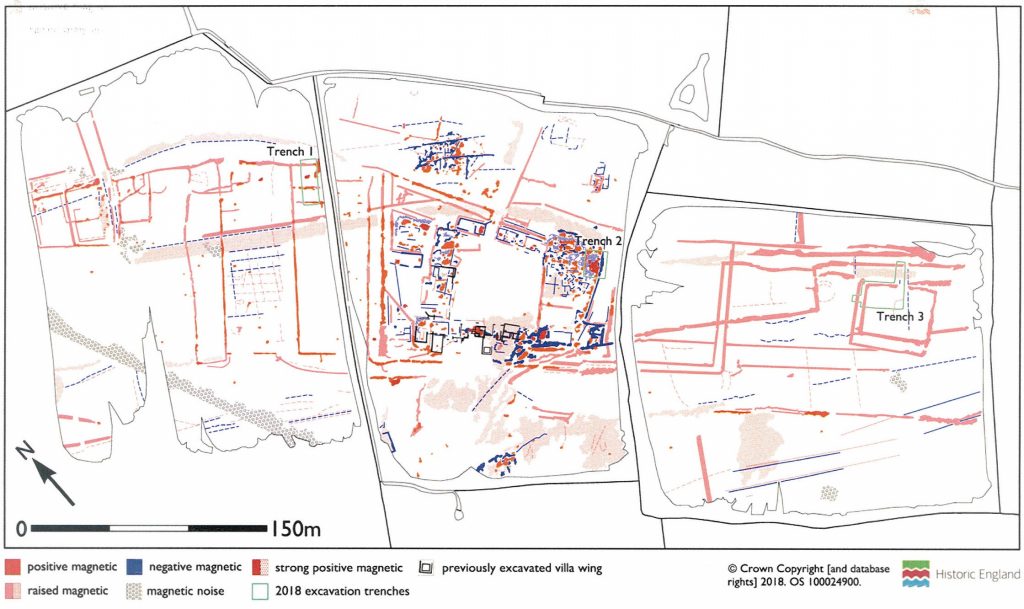

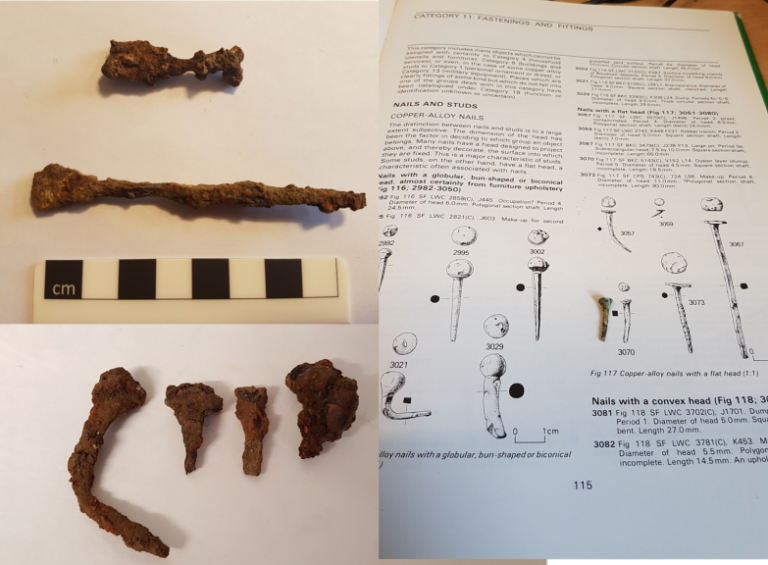

In 2018 David Roberts from Historic England led an excavation which attempted to characterise some additional enclosures and buildings newly revealed by magnetometry (Figure 4). In his talk, he swiftly ran through what the three trenches had revealed (not much) and Nicola Hembrey, also from HE, showed a few slides of finds – many iron nails, a lovely Mesolithic flint and small bits of jewellery.

It seems that the HE investigation was prompted not so much by the importance of the site, but by a window of opportunity offered when another excavation fell through. The aims were to understand other parts of the villa site (HE did not excavate the villa itself), check out a possible cemetery (it wasn’t) and to provide training for different groups of workers.

TR1 had a series of aligned ditches and a possible grain dryer which seemed to have recycled stones from the villa. TR2 was a long wall attached to the end of the villa. Many tesserae were found, but none in situ. This trench had a considerable burnt area and seems to have had a life as a small industrial site. TR3 had three roundhouses with some anomalous features and several post holes. That was pretty much it for the recent work! Although the aims of the investigation were realised, the undertaking lacked the impact of the earlier excavations; to paraphrase Graham Greene: reverence and a good archaeologist are not enough.

Steve Parker – Natural England & SANHS

Steve Parker gave a presentation on wildlife in the Somerset Levels which was enthralling, wide-ranging and included the find of the rare large marsh grasshopper in various locations on the Levels in this summer (Figures 8 & 9).

Steve also incorporated some history as well as news. As we know, Somerset’s Levels and Moors have been constantly exploited, altered and managed by humans over the last 10,000 years leaving behind a uniquely rich archaeological heritage, including prehistoric track-ways and lake villages, miraculously preserved in the waterlogged peat. Dramatic changes have happened in the last 50 or so years in which large scale extraction of peat for horticulture has left a damaged landscape in many areas. Peat and peat digging has formed a fascinating social history which was at the heart of the local community across the Levels (Figure 10). Since the 1990s most of this abandoned countryside has been transformed into wetlands for wildlife.

Remarkably, our early ancestors would have recognised these restored environments, full of lakes, reedbeds and mires. Many of the reserves which now dot the Somerset countryside are still in the process of development both to generate suitable habitats to permit the return of disappeared species, in particular the bittern (Figure 11), cranes and otters, as well as more modest critters like the large marsh grasshopper. The restoration and expansion of habitats for plant species, such as the frog orchid and the veilwort are also key to establishing the richness of our Somerset heritage.

Mary Claridge

References

- The Buildings of England. Somerset South and West. Julian Orbach and Nikolaus Pevsner. Yale University Press London 2014

- Somerset parks and gardens after the Middle Ages: the archaeology of the formal garden, c 1540 – 1730 by James Bond.

- https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2008/25-april/books-arts/book-reviews/the-pious-equivalent-of-an-indoor-swimming-pool

Accessed 7th November 2019

Somerset Made Pots From The Last 100 Years

16th November 2019

Fiona’s Journey of 100 Pots in 100 Days

When Fiona Holmes, an experienced sculptress lost her creative sparkle to come up with new designs, she decided she needed to challenge herself to re-energise that skill. Not wanting to waste that energy she decided on a sponsored pot throwing of 100 pots in 100 days. This was a daunting task as she had never used a wheel. All sponsored money was to go towards funding of the new website that SANHS was developing. Every one who sponsored her would be entered into a raffle to be drawn at a later date for one of the four best pots she produced.

On 16th November, the Cotleigh Brewery community room in Wiviliscome was packed to hear Fiona share her journey of not 100 pots, but 177, all of which were on display. Every one who bought a ticket was also to be entered in the draw which will take place at the William De Morgan talk in February 2020. We were entertained to a very lively journey. Fiona shared her pleasure at her first success, her frustration at being kept on the path of making cylinders by her tutor who is also her father, and the matter of fact way she viewed the pots that were a little less than perfect. Part way through her presentation Fiona gave umbrellas to people in the line of fire when she settled down to do a demonstration on a portable potters wheel. She needn’t have bothered, the clay stayed on the wheel. It did show the amount of concentration and energy required and another pot was added to the collection.

Much of what she learnt over the length of the project was shared with us, how different clays react when fired, the difficulty in obtaining and maintaining height, pointing out the tallest she had obtained against the beautiful pot of her fathers which was at least fives times taller. One of the pleasures Fiona has experienced is viewing and discussing pottery which is part of the SANHS collection and judging by her performance on the night, the project has achieved it’s aim of re- establishing that creative art. The variety of shapes and sizes will make it difficult to choose just four pots to raffle.

Following on from Fiona’s presentation, David Dawson who is a longstanding member of SANHS and also an expert on ancient pottery gave a power point presentation of some of the pottery found at various archaeological excavations. This too was very entertaining as well as informative.

Amal Kreshiei who is the archaeological curator for the SWHT was also present with a display of a variety of the pottery from the collections which generated a lot of interest. This gave people the opportunity to view objects from the reserve collection not usually on display, with a knowledgable person to answer questions.